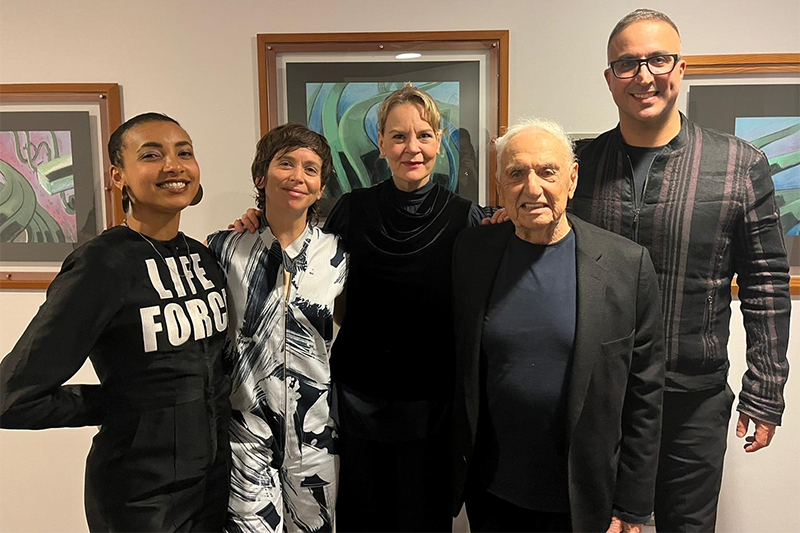

NY premiere of Double Concerto, for Esperanza Spalding, Claire Chase, and large symphony orchestra, New York Philharmonic, conducted by Susanna Mälkki, David Geffen Hall, March 2023. Photo by Chris Lee.

In the Artists’ Words

I don’t feel like a soloist in the piece; I’m more like a vein in the middle of a thick, undulating body.

When I used to play bass in orchestras growing up, I could feel myself on the outside of the sound being the feet of the dance. I’m placing this note here so that movement can happen. In the Double Concerto, everything I’m doing is interwoven with the orchestra, or it’s in an extemporaneous dialogue with Claire.

She’s a force of nature. There are moments when we are composing in real time simultaneously, and we don’t know what is going to happen next. I can’t really say what is going through my head. I hope not much, so that I can be present and responsive!

I feel altered by the landscape of Felipe’s orchestration. There’s a rush to my nervous system that I can’t quite explain. One of the challenges for me is not getting swept up in that sensation. I just want to stop and listen.

— esperanza spalding

Together, esperanza and I are like an octopus. Between our instruments and voices, we create a many-tentacled creature. The deep challenge is to be absolutely in sync with one another. It’s a totally different approach to the concerto that feels more like chamber music. When I first read Felipe’s flute music, I remember thinking that this person absolutely understands the vocal nature of instruments, particularly wind instruments. He’s inviting you to crawl inside and explore.

In the first part of the piece, you can’t distinguish my flute from esperanza’s voice. And you don’t necessarily know that I’m singing into the instrument. The resulting frequencies are a rich composite. Felipe also incorporated my glissando head joint, which elongates the flute via an internal slide. We found all kinds of juicy, unstable pitch material from overblowing in the middle and high registers.

Some sections of the piece are left entirely to me and esperanza. My definition of classical music is music that outlasts its maker, which includes spontaneous creations made on the spot and never heard again. When esperanza improvises, it leaves an imprint on the body of every person in that room.

— Claire Chase